Hypothesis

Kettlewell’s hypothesis for why dark Peppered Moths had become so common in polluted areas was as follows:

Dark Peppered Moths were better camouflaged against trees darkened by soot and pollution. This meant they were less visible than the light form to predatory birds, and so less likely to be eaten. In this way, the dark form could outcompete the light form.

The dark form Peppered Moth gained a selective advantage over the light form in these polluted areas.

Kettlewell’s hypothesis was based on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection: Individuals with traits that give them an advantage over other members of their species are more likely to survive to reproduce, passing on the genes responsible for these traits. Over the course of the generations, advantageous traits will become more common, and the species will evolve as its characteristics change.

Experiments

To test his hypothesis, Kettlewell conducted a series of investigations in the 1950s, including two field experiments:

Experiment 1

To investigate if dark moths have a selective advantage in polluted woodland because they were better camouflaged from predators than light moths.

Experiment 2

To investigate if light moths have a selective advantage in unpolluted woodland because they are better camouflaged from predators than dark moths.

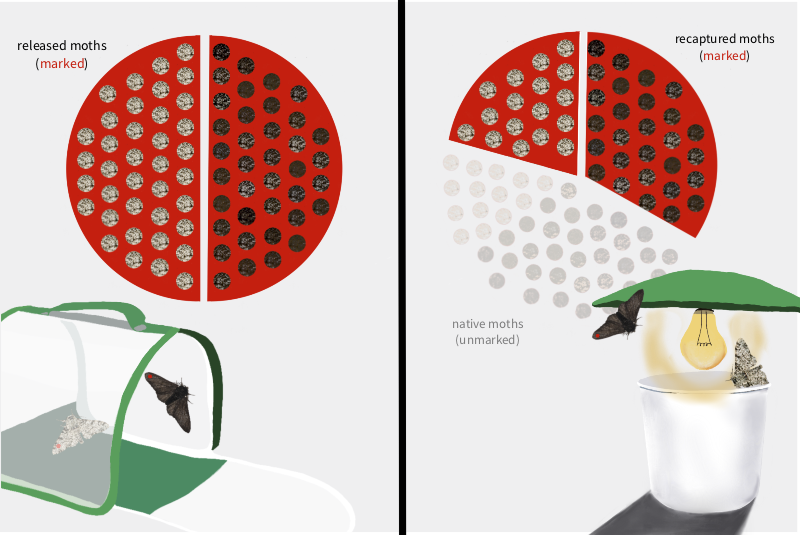

To compare the proportion of dark versus light moths that were eaten in each environment, Kettlewell used a technique known as mark-release-recapture. This involved releasing hundreds of light and dark Peppered Moths into woodland surrounded by natural boundaries, and attempting to recapture them two days later using light traps. These moths were subtly marked so that Kettlewell could distinguish them from any wild Peppered Moths he captured.

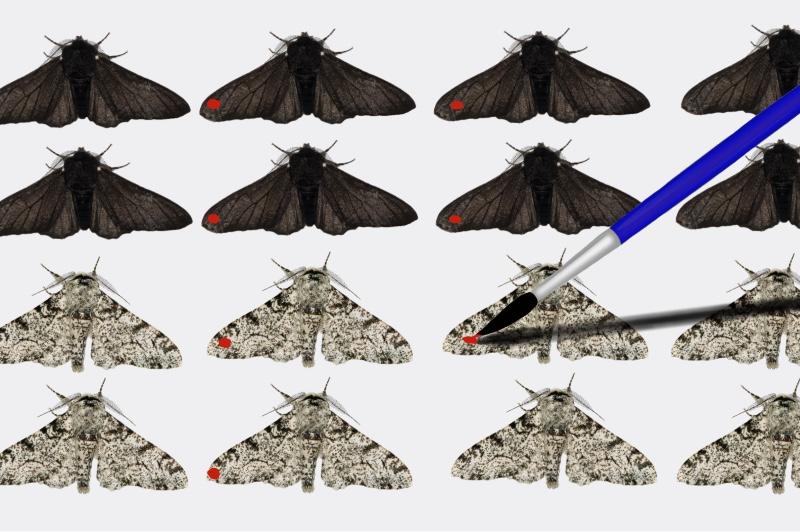

Step 1 of mark-release-recapture: Marking moths before release

Step 2 of mark-release-recapture: Marked peppered moths are released into polluted woodland

Step 3 of mark-release-recapture: A light trap is set up a few days later to recapture marked moths. Some native moths will also be captured.

Results: A greater proportion of dark Peppered Moths were recaptured from the polluted woodland, compared to light Peppered Moths.

Predictions

If Kettlewell’s hypothesis was incorrect, the light and dark moths would have the same chance of being eaten in each environment, and the number of dark moths would fall by the same proportion as the number of light moths. In this case, we would expect the following results:

- In polluted woodland, the proportion of light moths that were recaptured would be the same as the proportion of dark moths that were recaptured.

- In unpolluted woodland, the proportion of dark moths that were recaptured would be the same as the proportion of light moths that were recaptured.

However, if Kettlewell's hypothesis was correct, he woud have expected the following results:

- In polluted woodland, a greater proportion of dark moths would be recaptured compared to light moths.

- In unpolluted woodland, a greater proportion of light moths would be recaptured compared to dark moths.

Outcomes

Kettlewell's hypothesis was proven correct, and he found the following results:

- In polluted woodland, a greater proportion of dark moths were recaptured compared to light moths.

- In unpolluted woodland, a greater proportion of light moths were recaptured compared to dark moths.

The outcomes of these experiments gave support to the theory that British Peppered Moths had evolved by natural selection, and that, in polluted areas, the dark form had outcompeted the light form because it was better camouflaged from predators. Peppered Moths are just one species that exhibits industrial melanism, where species that live in areas polluted by industry evolve dark pigmentation called melanism.